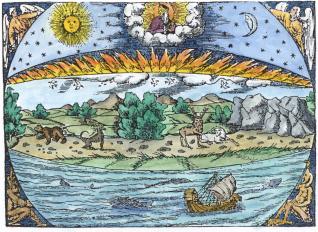

Sebastian Münster Cosmographia 1544

Science plays a central role in modern societies but science is not what most people believe it to be. Methodological foundations of science are nowadays unstable and scientists themselves are uncertain what these foundations are, if there are any. The matter is important because, as Russian philosopher Lev Shestov says, “the theory of knowledge is not at all an abstract, harmless reflection on the methods of our thought; it determines in advance the sources whence our knowledge flows.” One may say that ontology is dependent on epistemology and not the other way around.

The ancient Greeks distinguished between episteme (knowledge) and doxa (opinion) and were only interested in what could be known for certain. They were cognitive maximalists. Only episteme mattered while doxa was considered unworthy of attention of a rational being. A gentleman would not lower himself to thinking about ordinary matters which was the domain of the slaves. As a slave society, the Greeks held manual work in contempt while contemplation was considered the highest form of activity. Only slaves had closer contact with matter. As the Greeks believed that Logos (Reason) permeated that part of reality that really mattered, they thought that rational thinking was the key to understanding the world. Therefore, techne (craft) was for them inferior to episteme.

Moreover, as Alexandre Koyre explains, the Greeks thought that terrestrial, or sublunary, world was very different from the supralunar sphere. The former was the domain of corruption and change while the latter was governed by the laws of mathematics. As the Greeks believed that mathematics could not be used to describe the world of earthly matters, they were unable to develop techne into applied science. They were quite advanced in the mathematisation of astronomy but would consider the mathematisation of physics an absurd proposition because the sublunary world was imperfect, impure and changeable.

Theirs was a static society with no hope for progress. Aristotle was engaged in some rudimentary observation of physical objects while Plato devoted himself entirely to pure speculation. This frame of mind operated as a straitjacket on the Greek spirit.

Christianity continued the Greek philosophers’ disdain for earthly existence. Philosophically speaking, it was initially a form of Neoplatonism whose orientation was highly speculative. A significant change occurred in the thirteenth century when St Tomas Acquinas christianised Aristotle. Science, however, could not progress neither under Neoplatonists nor Aristotelians. The latter developed slavish devotion to Aristotle. His texts were considered more important than observation and supposedly contained all there was to know. There was no place for change in the Middle Ages. The medieval man looked towards the past and cherished permanence and immutability.

Only medieval technology made significant progress. As a religion open to slaves, Christianity gave recognition to manual work. The first centuries of Christianity were marked by the oriental form of worship involving asceticism and eremitic forms of monasticism. Eremitism was later replaced by cenobitism with monks not only praying but also working (ora et labora). Homo faber is a medieval creation and monks can be seen as proto-empiricists. Gothic cathedrals are a testimony to an intense engagement with the physical world in medieval times, albeit only among monks, craftsmen and artisans.

The modern world started with theoreticians like Francis Bacon and Rene Descartes and practitioners like Galileo. They created the model of science that lasted for three centuries, reaching its apogee in the second half of the nineteenth century and starting to crumble in the 1930s.

Rembrandt The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp 1632

A revolutionary change occurred when Galileo concluded that celestial bodies were also subject to change, limitations and imperfections. The discoveries of mountains on the Moon and the moons of Jupiter shattered the medieval worldview which was already crumbling following Copernicus’ calculations suggesting that the earth was moving around the sun. For Galileo, celestial bodies were but physical objects subject to the same laws as objects on Earth. Universal laws governed both the subblunary and celestial worlds. The sharp distinction between episteme and doxa thus disappeared.

Descartes provided theoretical basis for the mathematisation of physics and Galileo applied Descartes’ new method in his scientific experiments. He wrote in 1623 that “this grand book, which stands continually open before our eyes (I say the ‘Universe’), […] is written in mathematical language, and its characters are triangles, circles and other geometric figures”.

Galileo treated change as orderly and discrete therefore he needed exact calculations which could only be obtained by using precise measuring instruments. Senses were replaced by instruments in the observation of Nature. Until Galileo, people lived among objects that were apprehended by the five senses. Renaissance science introduced objects which could only be apprehended indirectly through instruments. Ordinary people still lived among objects that could be seen, heard, touched, smelled and tasted. Scientists however dismissed evidence coming from the senses as unreliable and focused on the objects that could only be observed via instruments. Visible objects moving in physical space were replaced by abstract objects moving in geometric space. Real existence of such objects was verified by theories, not senses; the status of these objects is even today questionable to some.

Theory replaced the everyday experience and common sense was no longer an arbiter of what was true and false. It was quite a challenge for people to accept that the Earth was moving around the Sun at an enormous speed without terrible wind pushing objects off the surface of the earth. It was also puzzling that objects thrown into the air fell on the same spot from which they were thrown. Common sense dictated that the Copernican model was absurd but science won the argument by appealing to the verdict of Reason emancipated from the yoke of ancient wisdom and metaphysics, but also from everyday experience.

It seemed that the marriage of Bacon’s empiricism and Descartes’ rationalism, or induction with deduction, was a perfect match that put the humanity on the path to knowledge that was certain and final – true everywhere and for all times. The Enlightenment strengthened that conviction and led to belief that all the fundamental questions raised by man will be eventually answered by science. Boundless confidence in science was quite common among the educated members of the society.

This model of science existed for three centuries. At its apogee in the second half of the nineteenth century, it usurped the right to all-encompassing knowledge of all human matters. Scientism penetrated into the areas that could not and should not be mathematised like psychology, sociology, anthropology and history which deal with human behaviour.

Joseph Wright of Derby An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump 1768

A reaction to scientism found its best expression in the thought of Wilhelm Dilthey who proposed to distinguish between Naturwissenschaften and Geisteswissenschaften whose aims and methods were different – explaining and understanding, respectively. The neoromantic criticism of science was based on the conviction that science was inimical to values, and alienating man from the world. Artists were natural enemies of science and literature abounds in expressions of hostility to science. Tolstoy writes in The Death of Ivan Illich that

The syllogism he had learnt from Kiesewetter’s Logic: “Caius is a man, men are mortal, therefore Caius is mortal,” had always seemed to him correct as applied to Caius, but certainly not as applied to himself. That Caius – man in the abstract – was mortal, was perfectly correct, but he was not Caius, not an abstract man, but a creature quite, quite separate from all others. He had been little Vanya, with a mamma and a papa, with Mitya and Volodya, with the toys, a coachman and a nurse, afterwards with Katenka and will all the joys, griefs, and delights of childhood, boyhood, and youth. What did Caius know of the smell of that striped leather ball Vanya had been so fond of?… “Caius really was mortal, and it was right for him to die; but for me, little Vanya, Ivan Ilych, with all my thoughts and emotions, it’s altogether a different matter. It cannot be that I ought to die. That would be too terrible.”

Dostoevsky is even more direct in his attack on science and its dehumanising effect in Notes from Underground

Upon my word, they will shout at you, it is no use protesting: it is a case of twice two makes four! Nature does not ask your permission, she has nothing to do with your wishes, and whether you like her laws or dislike them, you are bound to accept her as she is, and consequently all her conclusions.

Merciful Heavens! but what do I care for the laws of nature and arithmetic, when, for some reason I dislike those laws and the fact that twice two makes four?

… But yet mathematical certainty is after all, something insufferable. Twice two makes four seems to me simply a piece of insolence. Twice two makes four is a pert coxcomb who stands with arms akimbo barring your path and spitting. I admit that twice two makes four is an excellent thing, but if we are to give everything its due, twice two makes five is sometimes a very charming thing too.

… Consciousness, for instance, is infinitely superior to twice two makes four. Once you have mathematical certainty there is nothing left to do or to understand. There will be nothing left but to bottle up your five senses and plunge into contemplation. While if you stick to consciousness, even though the same result is attained, you can at least flog yourself at times, and that will, at any rate, liven you up.

These attacks were from outside of science and had little impact on it. A more powerful blow came from philosophers of science who questioned its methods and foundations. The last valiant attempt to put science on firm ground was made by Husserl who wanted to give science absolute certainty. “What is true is true absolutely, in itself; the truth is one, identical with itself, whatever may be the beings who perceive it – men, monsters, angels or gods”, he writes in Logische Untersuchungen.

His uncompromising maximalism could not be defended when there was growing evidence of science being a historical phenomenon. Thomas Kuhn destroyed the myth of science as a process of accumulative growth of knowledge which is expanding by adding one discovery to another. He showed convincingly that there was no steady progress in science which in fact changes through one paradigm replacing another. Karl Popper replaced verification with falsification, claiming that knowledge is always of provisional nature. Paul Feyerabend rejected all forms of authority, including the authority of reason and denigrated science as base and of little consequence.

The history of science is no longer perceived as linear and rational. Scientific criteria change through the change in paradigms, and scientists have difficulties with deciding what is scientific and non-scientific and what is rational and irrational. The boundaries of science are now porous. No-one believes anymore in trans-historical existence of the scientific method.

Polish philosopher Stefan Amsterdamski writes that for three centuries

… science has been treated as the embodiment of human rationality. It was seen as a feature specific to our culture, and its development was represented as the result of a systematic application of the rational method of investigation […] unlike the scientists and philosophers of a century ago, we no longer possess the conviction that scientific knowledge can be fully objective, as an unmediated product of an autonomous knowing subject, and that its history is simply the history of Reason.

The ship of science has entered unchartered waters and there is no land in sight.

(based on Stefan Amsterdamski Między historią a metodą and Jozef Zycinski Język i metoda )